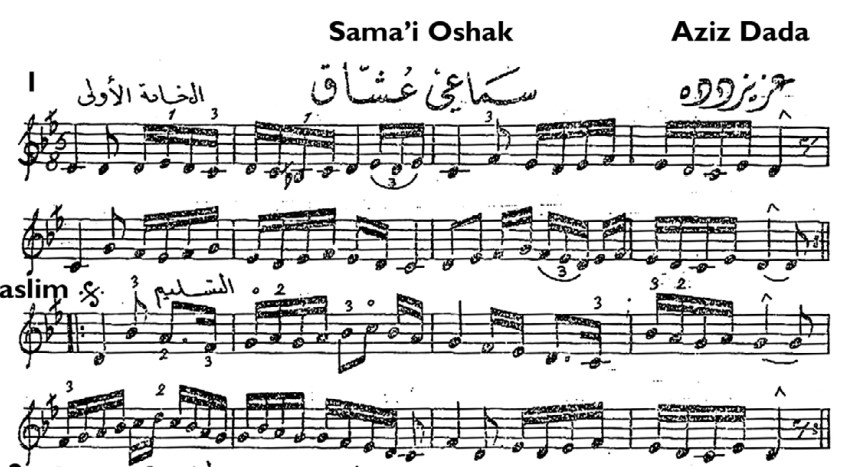

A fascinating phenomenon in middle eastern music is that we have in Arabic and Turkish repertoire some shared repertoire that originate from the Ottoman school of music that permeated their way into Arabic music. However, these pieces are generally performed in such a way as to demonstrate a unique aesthetic.

An important distinction between Turkish and Arabic renditions of the same composition are in the intonation of microtones employed in maqams rast, bayati, sikah for example.

There are also an interesting set of Ottoman repertoire that seems to have caught on rather strongly in the Arabic music sphere.

These pieces are performed with distinct intonational differences, particularly the renditions of pieces in maqam Rast.

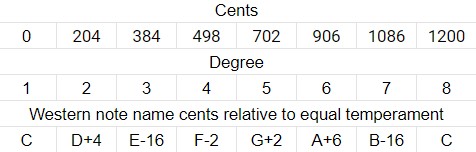

In general, the Turkish perform Maqam Rast with the 3rd degree and 6th degree about -16 to -25 cents flatter than equal temperament. One of the greatest musicians of the Turko-Persian sphere of influence, Abdulkadir Meragi defined maqam rast as follows:

The Arabs play Rast 3rd and 6th generally flatter. Between -40 to -60 cents flatter than equal temperament.

I personally play Rast with my E and B at about -45 cents flatter than equal temperament, but it can fluctuate.

So I wondered why are certain Ottoman pieces continue to be performed as part of the traditional (aka, turath) Arabic repertoire and but not others from the repertoire of maqam rast.

So I actually tried playing various pieces in maqam Rast with Turkish intonation and then again with Arabic intonation (generally flatter). And I realized that some melodies just DONT work with Arabic intonation to the degree that it’s unrecognizable.

Here’s an example. There’s a beautiful piece by Dede Efendi (of whom some saz semai compositions are performed in Arabic tradition) called Rast Sarki “Yine bir gülnihal ald? bu gönlümü”.

Try listening to the Turkish version: https://youtu.be/cJY7tbks15w

Then attempt to play it with Arabic intonation.

The contrast is jarring to say the least, when you hear the intended intonation first.

Below is a simple rendition on Oud in two intonations of maqam Rast.

To this effect the Arabic version of Maqam Rast has a completely different vibe. And thus, some melodies work, and some don’t. The intention of the composer is important. Dede Efendi required the use of specific intervals to convey the meaning he intended in the melody he uncovered. Intonation and intention influence one another.

That’s how I reason that some repertoire is shared and other’s are not. Why some maqamat don’t even get featured in the Arabic tradition. There is an aesthetic to each region that influences melodic and interval choice.

I’ve also heard Sami Abu Shumays, co-author of “Inside Arabic Music”, in an interview with Amedeo Fera describe microtonal intonation in the Arab world being generally sharper at the beginning of the 20th century, and that it became flatter. I need to get around to asking him for listening examples.

From this other questions arise for me.

What was the original intervals intended for Maqam Rast? Does Abdulkadir Meragi’s treatises on music provide answers?

Why did these change in some regions, and when?

So, now it’s your turn. What do you think? Leave a comment below.

If you liked this blog post, then you might enjoy this one.

Want to hear from me more often, sign up for my newsletter.