After many years of knowing this intuitively, I’m finally saying it out loud… the Oud has no place in Persian music. Well, to be more specific, Classical Persian Art Music.

Before I go any further, I want to add that this an opinion piece. I haven’t read many historical books or gone into first hand sources on this subject. I’ve only read what has been passed down in encyclopaedias and what’s been orally transmitted to me from my teachers. I’ve approached this from my experience PLAYING and DOING music, not from reading a book. I have drawn my own conclusions and I acknowledge there are counter arguments.

Part 1

The Oud disappeared from Persian music at some point and the legacy of long necked lutes continued in Iran and Central Asia during the medieval period until the 20th century when the Oud was revived in Iran.

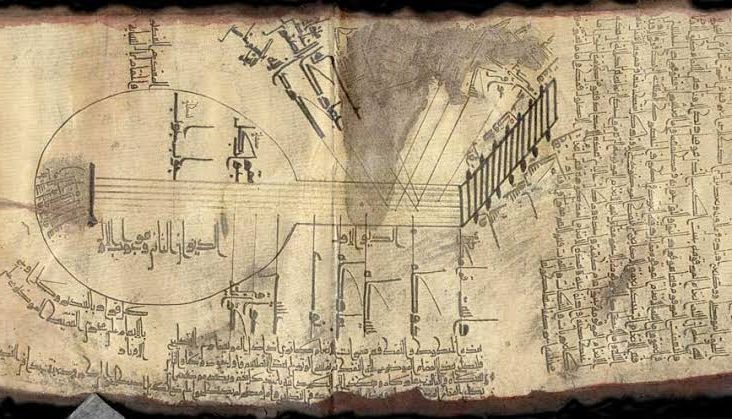

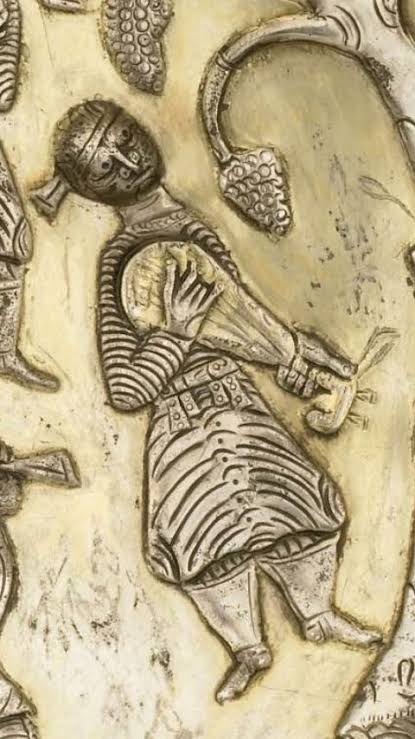

It was well attested in Iran that the Oud originated from ancient Persia and was adopted by Arabs during the middle ages. But we really don’t know what the instrument was like at the time. We know what Al-Farabi’s Oud was like but this Oud looks very different from the Barbat depicted in the earliest evidence from pre-Islamic Iran. It’s likely that the instruments used during ancient and medieval periods had no consistency in construction and were likely called different names by different peoples even from village to village much lesson civilization to civilization.

Ultimately, I don’t think we can take these depictions very seriously.

The Oud largely came back into Iran as a result of a desire to retake the Oud back from its Arab adoption and re-establish a Persian connection with the instrument. There is much legend around the Oud during the Golden Age of Persia just before the Islamic conquest and there is a desire to reconnect with that time before Islam.

But was that Oud really the Oud we know today? I highly doubt it.

My teacher Hossein Behroozinia is largely responsible for really re-establishing the Oud (AKA Barbat in Iran) in Iran. He decided it was his mission to bring it back while he was studying music at Tehran University. He majored in Oud, and he chose Oud as his 2nd instrument. But he then decided to change his primary instrument to Oud. This was not common during that time. The Oud was not looked upon as a serious study (with good reason as I’ll discuss later).

Why did the Oud disappear?

No one really knows… A friend of mine said something really brash and stupid. He said, “Persians sucked at the Oud so they invented the Tar”.

What? Seriously? What complete garbage. (I think he was trying to make a joke)

What if it was the other way around?

What if the Oud sucked for Persian music?

After studying the Oud/Barbat with Hossein Behroozinia, and performing Barbat with various Persian ensembles, I started to become disenchanted with certain obstacles the Oud had in the context of Persian music. Keep reading for the details.

Part 2

The Persian music we have today was truly formulated and established from the 18th-19th centuries in Persia. This period would have encompassed the Zand and Qajar dynasties. During this period and prior, Persian music was dominated by long-necked, fretted lutes like Dutar, Kurdish Tanbour, Setar, Robab, and subsequently Tar.

We do not know much about the origin of the Tar, but it soon became the foundation of Persian music. One of the important features of Iranic instruments from Kurdistan to Tajikistan is the presence of moveable, gut frets.

We also know that the ancient Barbat had frets and fewer string courses. Other instruments derived from the Barbat such as the Chinese Pipa, and Japanese Biwa also have frets.

At some point, the Oud in the Arab world lost its frets.

I started to realize the importance of frets in playing Persian music as I advanced on the Oud. When studying the Radif with Hossein Behroozinia I soon realized that Barbat players needed to work much harder to recreate the same Persian sound as passed down in the Radif. The embellishments and nuances don’t come out properly on the Oud. You can do it, and you can do it well. But it doesn’t have the same sparkle as when played on a Tar, or Setar.

Resonance

Another thing I started to realize was that playing the Oud was becoming very awkward. The sympathetic resonance and the tuning of the open strings often clashes with the Dastgah being played. The fundamental and tonic and particular sound of the open strings is carefully programmed into Tar and Setar tunings. And this sound was imprinted in my heart from childhood listening to Persian music. Not being able to hear the same sound while playing the Oud was confusing and disappointing.

This is common in modal music from Kurdistan to India, and Turkish Central Asia. You often play one mode for a certain period of time, and rarely modulate. Playing a different mode often requires re-tuning. While there are limitations in this versatility, it was rarely important in ancient music.

Arabic and Turkish music modulates often and quickly, the tonal center can change easily. The Oud achieves this effortlessly. This is what I think is the main strength of the Oud. In addition, Arabic and Turkish melodies are more dynamic and move around. They do not rest on the tonal center as long as in Persian music. This creates less need to have a certain resonance echoing through the instrument.

Persian musical instruments need to always make reference to the tonal center. The instrument itself needs to do this because we don’t use an instrument like India Tambura to provide that backbone. In Persian music, compositions are continuously divided up by rhythmical refrain (called “payeh”, the “foot” or “base”) that emphasis the 1st degree, 4th degree and or 5th degree. The Oud is not adept at this because of its lack of sustain and resonance. Modern Ouds are now built to sound less dry, but it doesn’t compare to the drone of a well programmed open string.

Playing a sparse rhythmical melody or payeh on the Oud is less satisfying than when played on Tar, Setar, or Kamanche because the Oud doesn’t fill the space as nicely as Persian music needs to create the right atmosphere. This is especially pronounced when those essential tonal center notes are played on closed positions on the Oud. The lack of frets results in less resonance and clarity.

This makes the Oud ill-equipped to compete with Tar and Kamanche or add value to a Persian ensemble.

The dynamics of a Persian ensemble are problematic to begin with. But the timbre and frequency range of Oud in comparison to instruments in a Persian ensemble make it a poor bass instrument, and a poor solo instrument which doesn’t cut through a Persian ensemble.

After years of playing Oud in different Persian ensembles, I grew frustrated that the Oud was never heard. I grew tired of hearing from audience members that they couldn’t hear the Oud.

Part 3: Where does the Oud shine?

So what to do about this conundrum the Oud finds itself in?

I think there are some solutions.

- Oud and Setar ensemble combinations. Oud and Setar compliment each other very nicely. The Setar provides the high end frequency response, and the Oud provides the midrange. The Setar provides the tonal drone required to fill the space and atmosphere while the Oud provides strong melodic backbone to the Setar’s small sound.

- Oud and Ney combinations. The Oud and Ney both have limitations. The Ney lacks certain notes and the pitch of notes might vary. The Oud and Ney should be able to be more flexible to match pitch as opposed to fretted instruments. The long notes of the Ney fill the space and the Oud provides a percussive sound to the long notes of the Ney.

- Southern Iranian gulf music. The Oud is just so right for this music.

Mechanical Solutions:

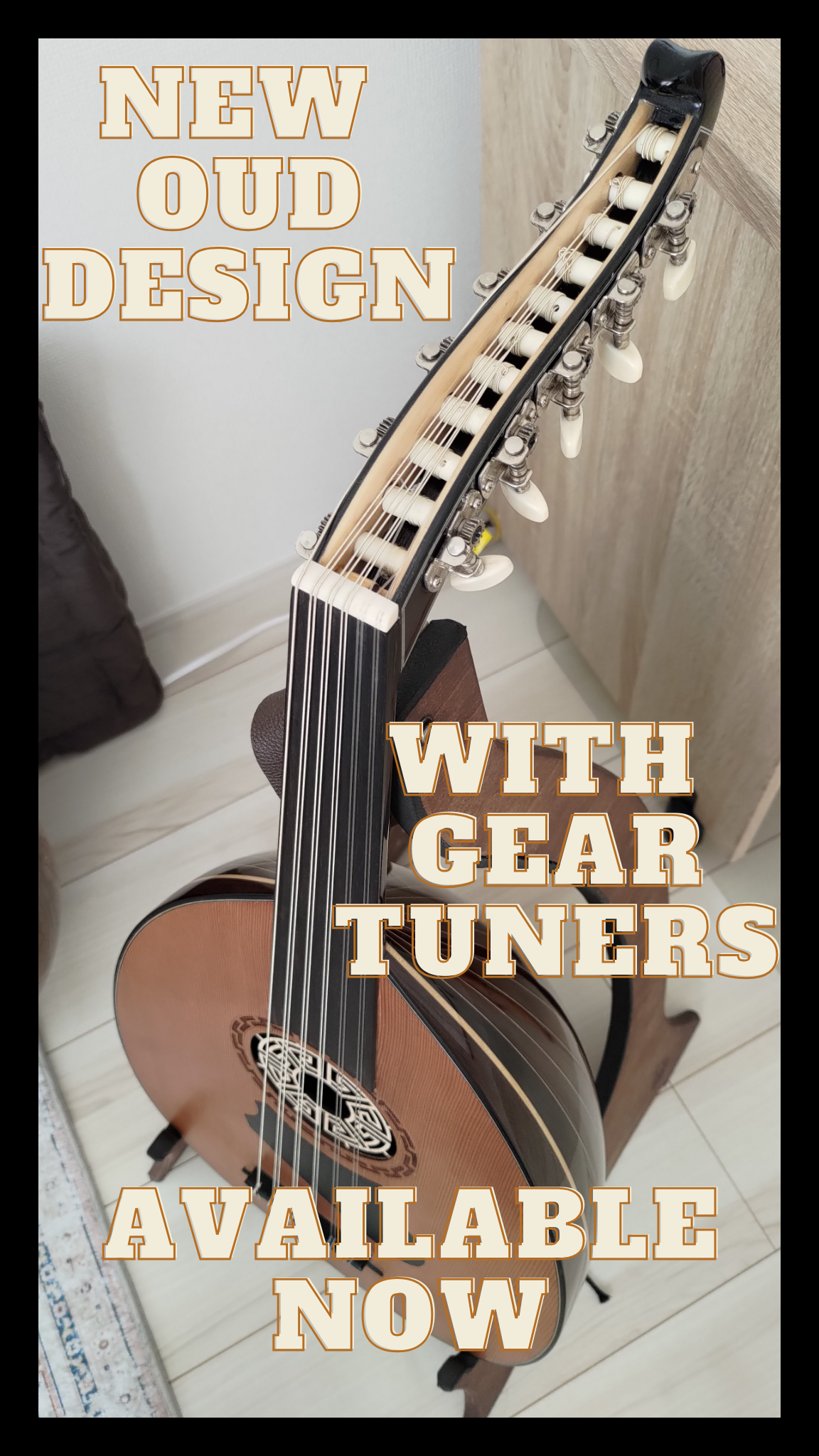

- Let there be frets. Persian Oud can be enhanced by gut frets like Tar, Setar, Buzuk, Baglama Saz etc. This solution has its own drawbacks too. But the Oud will be alive with the ability to play more like a Tar or Setar and with greater clarity and projection. This would be more in line with the ancient origins of the Persian Barbat anyway. Said Chraibi designed and commissioned an Alto-Oud which also has frets. The result is outstanding.

- Using floating bridge FADgcf tuned Ouds in Persian music. Persian instruments are all floating bridge instruments, so why not the Oud? Floating bridge Ouds provide a more modern sound, and less dry sound. Floating bridge Ouds sound more in line with Persian instruments. The increase of range would allow for greater penetration in Persian ensembles.

As you can see, there are some easy ways to overcome some of the challenges the Oud has in Persian music.

While a lot of the challenges with sound production ultimately rest with sound engineers, I’m more interested in the feeling and spirit of the instrument and the history of the Oud which influences the sound produced and its capabilities. The structure of the Oud and the tastes of the peoples using the Oud influenced each other in such a way that now the Oud is most ideal for Arabic music whereas the Piano is not. Likewise, the Oud may not be ideal for classical Persian Art Music.

I say, that’s okay. The Oud is what it is.

What about the material of strings used in oud compared to tar or saz? Would that make oud sound completely different or would it enhance the resonance?

I wonder. I think it’s worth a try, but I’m not sure light gauge metal strings would sound very resonant on a wood fingerboard. They get muted too much, as I’ve tried this on my fretless mandolin.