The other day I received this very good question from a student from the Step-by-Step Taqasim program:

“Hi Navid,

I noticed that on the first page of this Taqsim, all the B’s in the bass part are B quarter flats. Yet the Bayati scale and key signature shows the B to be a simple Bb. Could you say why the quarter flat is used here and not Bb? With a B q flat and an E q flat, isn’t this more like Rast than Bayati?”

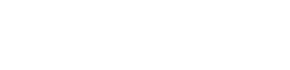

He’s referring to this beautiful taqsim played by Simon Shaheen. In my Step-by-Step Taqasim program, you get access to the sheet music for it and learn how it’s played:

So this taqsim is in maqam Bayati, but he uses a lot of B quarter flats, which you wouldn’t see in the key signature for Bayati.

So why would he use B quarter flats in this taqsim?

Here’s my response:

“This is very difficult to explain, but I will do my best. Let’s imagine that a maqam is NOT just a defined set of notes in a sequence, but rather a set of notes with an additional subset of notes that can be used to deviate from the scale without deviating from the vibe of the maqam.

The open course D which forms the tonal center for maqam bayati creates a lot of gravity. It pulls notes towards it. This open D has more density and pull than the D in the higher octave and the lower octave. They are not equal. That open D string is the beginning and the end of the maqam. (In other maqams this can sometimes be different). It’s like a super nova and a black hole. All the melodies explode forth from it and get pulled back into it.

It’s conventional for B quarter flat to be used in that lower register when moving toward the tonal center. This occurs in Persian music, Turkish music and Arabic music but sometimes in different ways. It’s a modulation that keeps reiterating the tonal center D in maqam bayati, and the reason why B flat is not used is that the pull of D pulls B flat higher so that it becomes B quarter flat. This is my speculation and just a way of making sense of it.

B flat is too far from D to make those melodies work for some reason. It just doesn’t sound right. B flat rather pulls the melody in a more descending pattern. Not always… but usually. B quarter flat pushes the melody in an ascending fashion. You see this is maqam hijaz too when you use B quarter flat on the way up the octave and B flat on the way down. Of course, there are all exceptions to these ideas.”

So during a taqasim where you want to return to and emphasis the root of the maqam from the tetrachord below the root, you can sometimes use an accidental. You can’t just use any note you want. It should be conventional. But there is some freedom. You can view the root of the maqam you started in as the 4th note in a new tetra chord that extends below the root. So let’s take Bayati on D…

You could experiment with the following notes below D:

A Bqb C D(the root of Bayati) – Note: (AKA jins Bayati on A)

A Bb C# D – AKA: Jins Hijaz on A. Note: when using this tetrachord it may be risky to use a note below C# as the quality of the vibe will change drastically with such a large interval.

A B C D – AKA: Jins Busalik on A. Note: The effect will sound close to using jins Bayati on A.

Use these tetrachords when ascending to land and focus on D (the root of Maqam Bayati). That’s the most straightforward way.

How this is used in Persian music

In the Dastgah system of traditional Persian (Iranian) music, using a tetrachord below the root of a scale would be considered another “gushe”. A dastgah in Persian music has many “gushe” (meaning: corner, or niche. Also interpretable as “mode”.). These gushe inform the melodic developments that can occur within a Dastgah. So if a new tetrachord was introduced in such a manner it would have a name and a specific melody attached to it, and perhaps a focus around a certain note. A Dastgah is more than a scale or a mode or a maqam. A Dastgah has a bunch of modes (gushe) within it that have a range of characteristics, and has to conclude in a certain way.

Coming from Western music, one tends to view scales as cyclical… CDEFGABCDEFGABCDEFGABC… etc ad infinitum…

But in middle eastern music and other modal music the range of pitches are often not more than 2 1/2 to 3 octaves. The range of instruments were limited which makes the certain notes in a maqam more important and have more value.

In other words, coming from western music we can sometimes think that D2 is equal in value or force as D3 (even though they are an octave apart)… But I argue that in middle eastern music, a note’s weight, value and force depends on the range of the instrument(s) being used. On the Oud, for example, D3 when playing maqam Bayati is far more important than D2. The reason for this is that we have a certain range of notes in relation to D3 that give context to the melodies available to be played, the nuances made possible, and the overtones being heard on the Oud.

This is in high contrast to a piano where you have so many notes available in many octaves that you can create these musical relationships anywhere which actually makes any one note even less important.

This is perhaps why certain instruments favor some keys more than others. Some keys are easier to play, some keys just sound more full and have a greater range of playability.

It’s like real estate, the less notes available, the more real estate each note has.

If you’re interested in learning more about playing taqasim, I have more tips and methods to share with you next week, so be sure to sign up for my newsletter below:

Click here to sign up for my newsletter and get more taqsim tips

And while you wait for more taqsim tips… what are you thoughts? What other “conventional” things in Middle Eastern music have you noticed?